Designing an insurgency wargame – Part 2: The Environment

In my previous post, I discussed in general terms my objective in designing a new manual insurgency wargame and some of the basic concepts it should seek to simulate. I know this is a very belated follow-up, but in the meantime I have been learning Python and considering turning this project into a computer simulation. That would be a daunting task, so for now I am sticking with the manual format with the aim of turning it digital down the line.

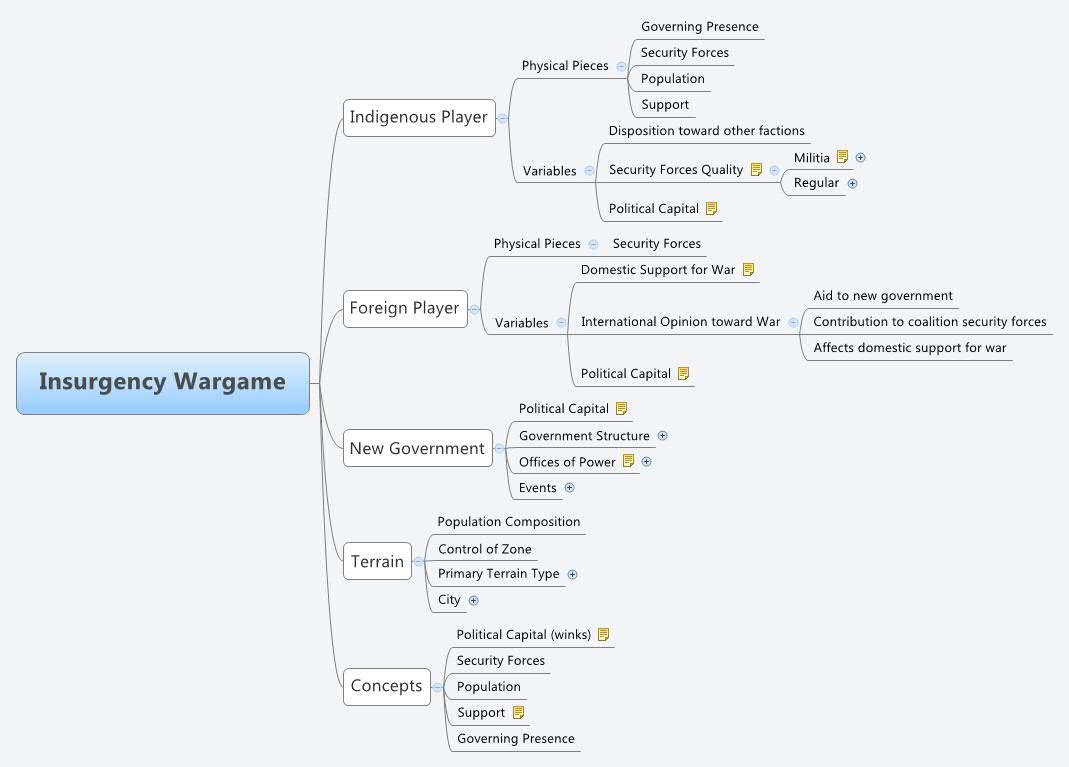

The wargame can be divided into roughly two realms: the environment and the players. In this post, I’ll discuss the environment and mechanics involving it.

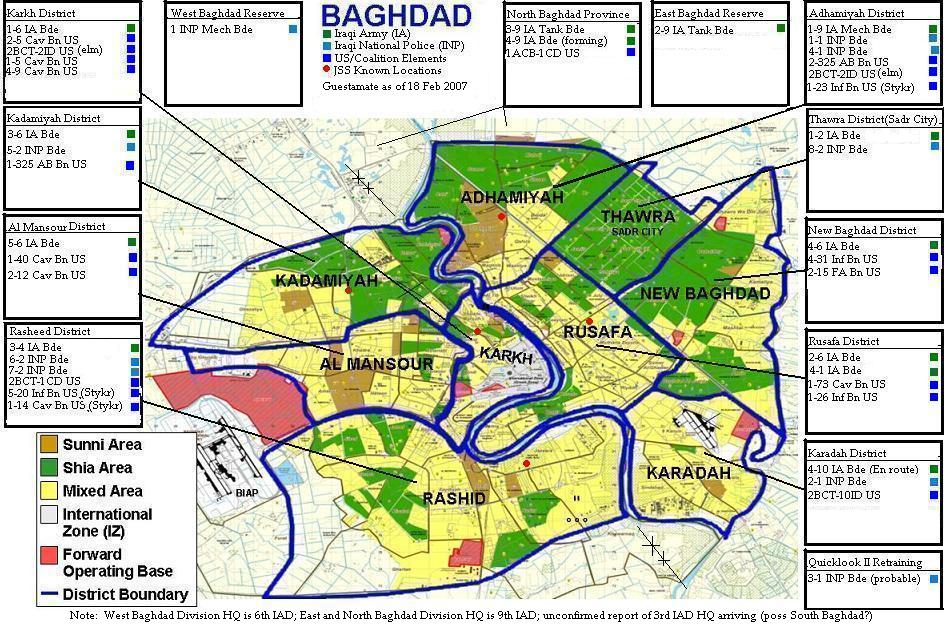

The environment is divided into regions at a level that make sense for the design of the scenario, whether that be villages and neighborhoods, cities and towns, or entire provinces. Choosing this lowest level of representation is a balance between complexity and utility; representing politics or combat at the provincial level involves far more abstraction and less choice than representing them at the local village level.

The main feature of the environment is terrain, and for simplicity each region contains a single type of dominant terrain. In this simulation, terrain will affect the results of combat events and the amount of effort required for a faction to gain support in a region. Each region also possesses a certain level of urban build-up, from none (uninhabited) to extremely dense. As expected, this affects a regional population’s size and demographics, as urban populations are more likely to contain significant diversity. This allows the possibility of an urban/rural divide among insurgent or loyalist factions.

Regions possess an objective value based on factors such as economic output, fertile land, presence of resources, etc. The subjective value of a region depends on a particular faction’s objectives and requirements, which are not necessarily known to other factions in the game. For example, a nationalist insurgent faction may have no interest in controlling a prosperous region held by an opposing faction because it contains an incompatible population type and is not part of the historical nation the faction seeks to establish. (These factors are taken into account in the player’s victory conditions, which are on a card given to the player at the beginning of the game and cannot be shown to anyone.) Instead, the faction might use violence to suppress the region’s economic value to the enemy without ever seeking a local base of support. Discerning the objectives of other factions is crucial to the political aspect of the game, especially negotiations with enemies and allies. Insurgencies do not happen in a vacuum, so a scenario should include historical context that suggests each faction’s likely end-state goals and territorial aspirations, but the specific victory conditions are confirmed only to the player. In claiming a set of objectives to other players, a player can tell the truth or bluff, but other players can never see his card to confirm the truth.

Control over a region is determined at two levels. First, there are governing structures that determine what faction exerts official control of the region. Just as a military force is sustained by supply, governing structures require support of the local population to function, though this does not necessarily mean the government in question is representative in nature. Support can also be projected from neighboring regions, though local support or lack thereof naturally has a stronger influence. Structures by competing factions can exist in the same region, making official control impossible. Alternatively, structures by cooperating factions allow for split control based on whatever agreement the factions make (e.g. a federal system).

Second, a region can be effectively controlled with a military force presence that suppresses existing governing structures. The disadvantage, of course, is that militarily controlling a region requires constant presence, along with the usurpation of governing structures and the complete removal of opposition forces. On the other hand, military control is not dependent on the local population’s disposition, making it ideal for a powerful but foreign player attempting to restore or install a local ally into place.

Control of zones will play an important part in combat, as changes in control can affect “momentum,” a mechanic that will allow factions to capitalize their successes or exploit enemy missteps. Tactical retreat from a region may make sense to preserve a limited military force, but it will affect public perception about the conflict (especially for a foreign faction) and boost enemy confidence.

In the next post, I’ll discuss political mechanics.

Good start Robert. If I were you I would just try to get the game done NOW, in paper form, and worry about digital ports and programming languages later. Expend your brain cycles on this first.

Correct that there are different types of control of an area, and different degrees of control too:

– non-material control of the human terrain: “hearts and minds”, where you get the allegiance, hatred or withdrawal of parts of the population of a given area. Note that this can change quite independently of whatever the government or insurgent might do, and can be quite complex in its combinations and flux. I think I have mentioned the work of Stathis Kalyvas on this to you before.

– material control of the human terrain: concentration camps and “strategic hamlets”, both inventions of the British Empire, though restricting where the civilian population may live and travel and do its work has a long history (“they made a desert and called it peace”). Very difficult to arrange and may not make a great deal of difference in the end; all berms and walls are permeable.

– human control of the material terrain: taking and dominating the “high ground”, controlling the lines of communication and transit into and through an area.

– non-human control of the material terrain: think of this as “area denial”, and something that’s not often done, or done for long. Extensive minefields, the Morice Line, the McNamara Line (well, the idea behind it anyway), and the crazy plan to scatter radioactive material along the border with Manchuria in 1951 to keep the Chinese out.

And so on…

This looks interesting. I agree with Brian that paper-based is best to start with, for reasons of flexibility. I wonder if some kind of Excel spreadsheet would work as a halfway house? You could capture a number of variables for each zone (human terrain, various influence factors, troop density &c.) and model their interactions when one is changed. Then you could tweak the algorithm as required without any in-depth coding.

Look forward to seeing more.

Excel spreadsheets are a very good way to test out these kinds of linkages, and whether your algorithms are any good. You can assign and tweak all kinds of variables.

I started work on a web-based counter insurgency strategy game a couple of weeks ago (although I’ve been thinking about it for a lot longer). I found your site while looking for ideas and source material and I think your game ideas sound very interesting. I started off trying to do a very high level abstract game based around policies (nationstates.net style), and wondered whether I could get away without any kind of map at all – partly to get away from most computer games where it’s all about blobs on a map battering each other to total annihilation. Since then I’ve concluded that a map is necessary, partly to make it more engaging for players, and partly because regions and the differences between them are frequently a key part of COIN campaigns (inkspot strategies etc). I’m currently basing it on early Vietnam, specifically III corps as that’s a period I’m currently most knowledgable about, although I’m planning to make it fairly generic and bring in strategies that weren’t actually used much there to allow a bit more “what if” flexibility. Anyway, best of luck with yours, and I hope I can get mine to a state where it’s worth gathering some feedback (it’s a hobby not the day job, so progress will be pretty slow).

Sounds like a very interesting and ambitious project! I look forward to checking it out once it’s in a playable state. Let me know if you need a playtester at some point.