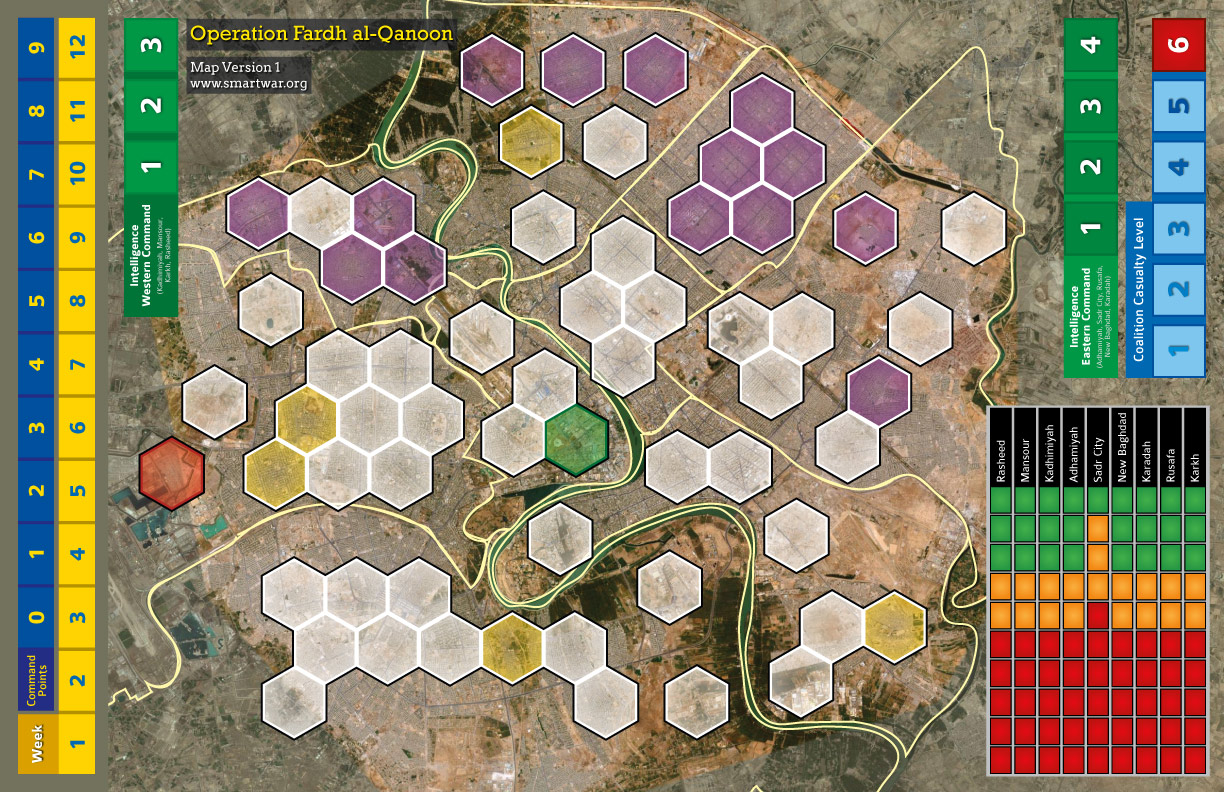

The elements of an Operation Fardh al-Qanoon simulation

I finished the first draft of my simulation rules for Operation Fardh al-Qanoon (aka the Baghdad Security Plan) more than a month ago, which I no doubt thought was exceedingly clever and put me ahead of the curve. After putting together a map and a draft of a historical analysis (as required by my Conflict Simulation course), I realized I needed to scrap everything and go back to the drawing board.

Unlike many of the other scenarios chosen by my fellow students, Operation Fardh al-Qanoon is not primarily about the combat. Combat is an element, but one that I focused too much on in my first draft rules. In its initial form, the simulation devolved into a game of whack-a-mole, with Sunni and Shia insurgents, al-Qaeda terrorists, and foreign jihadists playing the role of dastardly moles. Coalition and Iraqi troops obviously had a lot more on their hands than chasing and killing militants once the operation began in February 2007. No COIN simulation can be complete without a robust portrayal of the political dimension, and the political developments in Baghdad in 2007 were certainly interesting.

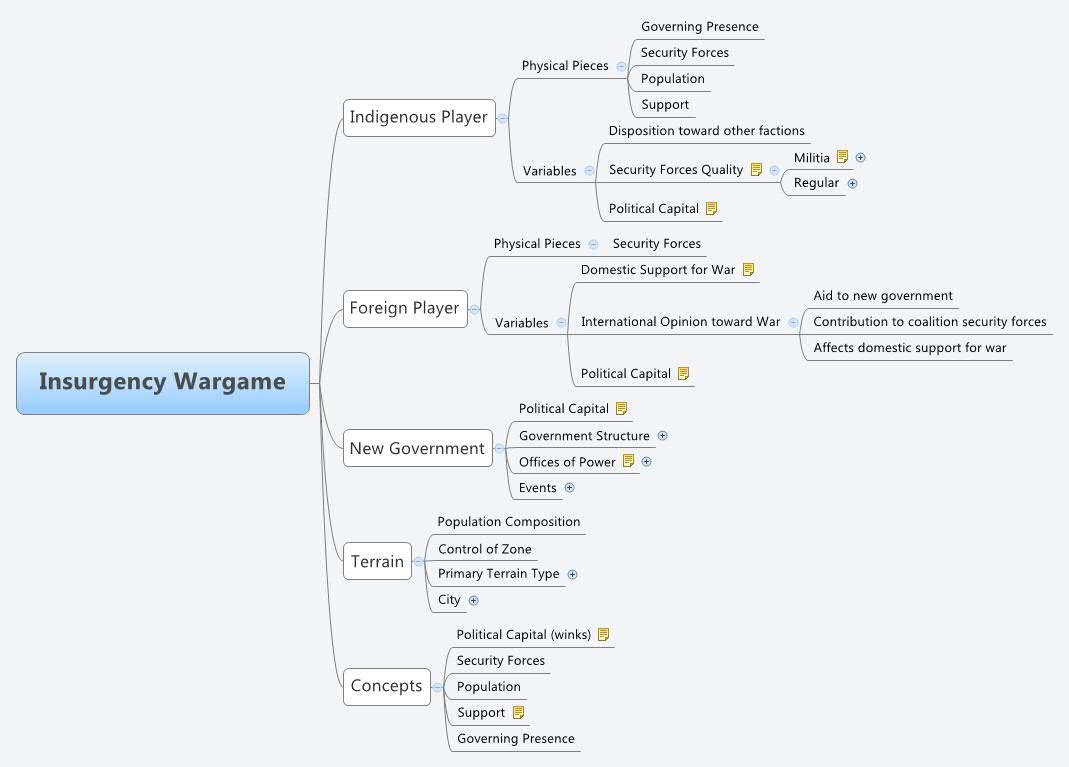

Players

The first element of a simulation is the actors involved. A classmate is designing a simulation of the 2008 terror attack in Mumbai as a solitaire game, which I think works well for that scenario. The Baghdad Security Plan practically demands an intelligent, responsive adversary, but the constraints of the assignment mean there can only be up to 2 players. I’m scrapping my plan to have an “OPFOR” player representing all elements working against the Coalition in Baghdad, as the only way to make it work would be to have very restrictive rules that force the opposition player to use his assets in a historically proper way (i.e. not having Shia militias cooperating with al-Qaeda operatives against Sunni civilians).

There will be a Coalition player as usual, but the opposition player will represent the Shia insurgency, specifically Muqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army. The Sunni faction, al-Qaeda, and foreign extremists will be handled by the “game system” through rules, so they will still be represented, but there won’t be an intelligent, actively-plotting personality behind them. A problem with this approach is that it makes it possible to “game” these factions, since the rules for their behavior are known to both players.

Simulation Dynamics

Like any counterinsurgency scenario, the Baghdad Security Plan was a contest between opposing political forces in an arena composed of people. At the same time, it was a battle of order vs. chaos. Regardless of who was “winning” faction-wise, high levels of violence and instability meant everyone lost. An ideal simulation would measure both factional support and stability (which takes security into account) within the 9 administrative districts of Baghdad, but given the constraints on complexity for this particular simulation, I will be measuring factional support only.

All other elements of the simulation, namely combat and politics, can be implemented through a relationship with the factional support system. Each player’s goal is to ultimately improve their relative standing in the city, and the other side of this coin is forcing the other player to take actions that make him lose support.

Unit Tactics

Uncovering a weapons cache (Source: Wikimedia)

A Coalition player has the basic options of patrolling neighborhoods to identify and remove militant forces, raiding insurgents & militants to remove leadership and material resources (when their locations are known), and building (a generic term for all reconstruction, development, and community engagement activities). You’ll notice combat is not listed as a primary activity, but combat does occur when a Coalition unit tries to clear an area of militants during a patrol action. Targeted raids are ideally meant to take out militant leadership or resources without a fair fight, but combat action requiring resolution can occur during a raid as well. The other option for combat occurs when the Shia militia player decides to engage the Coalition or another faction’s forces.

While the Shia player does not have the resources or highly-trained personnel of the Coalition, they have a larger base of human support to draw from, giving them men, materiel, and space for maneuver. The Coalition operates from an inherently vulnerable position, while the Shia player’s fighters, leaders, and equipment has a city of millions to hide in. The Shia player must decide whether to engage Coalition forces or Sunni & foreign extremists (or all of them at the same time), where to risk militant forces, and how best to maintain their factional support and increase it.

Say, for example, that the Shia player decides to shore up its support in a district and attract new recruits by using violence to drive Sunni residents out of a mixed neighborhood. This increases the chance of a Sunni reprisal attack against Shia civilians; the Shia player can use its fighters to protect Shia civilians and attack Sunni militants, but will then expose themselves to Coalition interdiction. By doing nothing, they give the Coalition an opportunity to fill the gap and gain factional support. Both players have an array of options at their disposal, and they can be as proactive or passive as they want.

The field of play: human terrain

The simulation takes place in the 9 administrative districts of Baghdad, offering a rather unique terrain. With most wargames, you would differentiate between plains, forest, and hills, but Fardh al-Qanoon will have to rely on human terrain. While there likely will be a differentiation between dense and less dense urban terrain on the game map, the most important feature of the map will be the demographic makeup of each represented neighborhood. I’m working off of the administrative and neighborhood districts outlined in this document (PDF), but many of the neighborhoods will have to be combined to form one “area” on the map for the sake of simplicity.

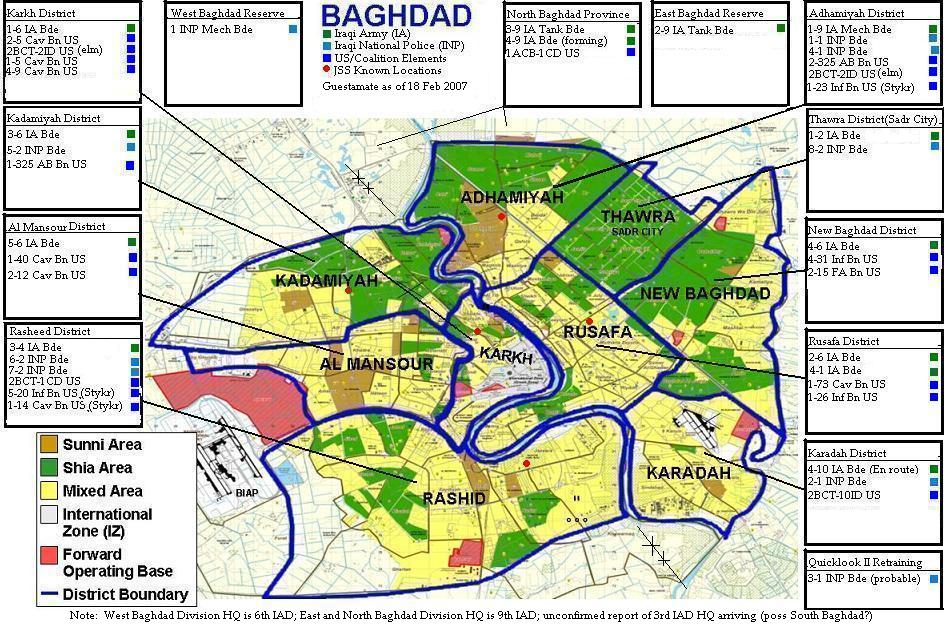

A map showing the Coalition Order of Battle in Baghdad in February 2007, with neighborhood demographics (Source: Long War Journal)

Some neighborhoods are largely populated by Sunni Muslims, others by Shia Muslims, and others still by a mixture of both. The Shia player aims to shore up their support in Shia and mixed neighborhoods, while trying to drive Sunnis out and prevent Sunni extremists from harming Shia civilians or holy sites. The Coalition player has to play a delicate balancing act between Sunnis and Shias, protecting both without favoring one over the other or becoming embroiled in open war with the Sunni or Shia factions. Al-Qaeda and foreign extremists will also require local support in Sunni or mixed neighborhoods, which they can lose if Sunnis in a district come to view the Coalition as a better option.

A measure of reality

The game “engine” has to be flexible enough to allow the operation to develop in any number of ways, the vast majority of which obviously did not happen in reality. The conditions of game victory are what will provide the incentives necessary for players to act in historically analogous ways without binding them to that course. The Shia player may decide not to temporarily stand down in February 2007 as US “surge” units start arriving in Baghdad (as Muqtada al-Sadr did in real life), and instead take their chances bogging Coalition forces down in ugly street fighting before all the new troops can arrive.

The game engine, under the limited influence of chance, will give the risk-taking Shia player a certain set of outcomes, most of which would certainly seem terrible for him in the Coalition player’s eyes. Such a move would certainly involve a heavy loss of forces for the Shia player, but if it manages to inflict massive Coalition casualties (and thus make the operation an immediate political failure) or forces the Coalition to abandon protecting the population in favor of fighting militants, then the Shia player can achieve its victory objectives.

My goal is to design a simulation that will reliably answer some “what if?” questions without being prescriptive. A COIN simulation is inherently difficult because COIN and anti-COIN advocates disagree on the underlying math behind a COIN operation, and thus they disagree on what the results would be. Was the surge successful because of an influx of US troops and the tactics they used, or because of the Sunni Awakening?

The questions behind a Fardh al-Qanoon simulation should not be about the efficacy of counterinsurgency. They should ask about the relationship between the various factions at play, about violence and stability, and about political support. By modeling the underlying dynamics, this simulation will hopefully be “valid” without having to make an initial assumption about whether COIN works or not.

1 Response

[…] match up with reality is creating the baseline for results in the first place,” wrote Hossal (http://www.smartwar.org/2011/12/the-elements-of-an-operation-fardh-al-qanoon-simulation/), who later described how he intends to measure the impact of the two sides- Coalition and […]